|

India’s Uncrowned Workforce: The Domestic Workers

Gitartha P. Bhuyan

India, a country with a population count of 1366 million has an economy which is driven by the sheer dedication and determination of a large manpower. Being the second populous country after China, it has a labour force of 487 million workers who earn their daily bread by engaging themselves in various informal and formal sectors. Out of that, two third of the workers are women who are informally employed as domestic workers in a very minimum wage and poor benefits. According to the International Labour Organisation, globally, the total number of domestic workers is about 67 million out of which 80% consists of women. In India, the number of female domestic workers is about 60 million.

Domestic work is associated with the worldwide history of slavery, colonialism and other forms of subjugation. Domestic work is defined as the work which is done in a household or for a household (ILO convention 189.) To speak broadly, domestic workers bear personal and household care according to the needs of the people. The tasks of domestic workers may vary from household to household where they may cook, clean the house, take care of the children and elderly or disabled, sit the pets or babies in full time, part time or in hourly basis. The pay structure of the domestic workers are thus made in accordance to their work. In India, domestic work has been conventionally placed at the rear end of the employment construct with low social status and institutional ignorance. They are a group of marginalised people who lives a precarious livelihood due to the utter ignorance and exploitation by the upper section of the society.

According to a book called Maid in India by Tripti Lahiri, there has been a spike in the number of female domestic workers between the age group of 15-59 from the year 2001 to 2011. In cities, the increase was over 70% from 14.7 million in 2001 to 25 million in 2011. As people are preferring for nuclear families now-a-days, the demand for domestic workers have raised substantially. With increasing prosperity among people, the demand for domestic help increases. As more and more Indian woman are entering the paid labour market in increasingly larger proportions in urban or sub-urban areas, they have to pay someone else to do the household care work they would normally do. This is where the domestic workers comes in. As there has been a decline in the agricultural produce and livelihood security in the rural areas, people from the rural areas migrate to the urban cities and engage themselves as domestic helpers. Despite their contributions to the informal economy and the households they work for, domestic work is situated at the low end of the care economy, working some of the longest hours, for very low wages. A report by the ILO published in 2018, has also noted a wide gender disparity in India’s workforce. “Female workers are paid a lower wage rate than their male counterparts in each employment category (casual and regular/salaried) and location (urban and rural), although the differences are smaller on an average in urban than in rural areas,” said the ILO’s India Wage Report. The National Sample Survey Office’s 2017 data show that the average daily wage rate for non-agricultural labourers were ₹271.17 for men and ₹205.90 for women, or 24.06 percent lower. The lower wages are now likely to further push women into poverty and increase their dependence on male relatives. 50% women workforce belong to the category of domestic work across the world and it is a fact that they contribute to the economy of the world.

The domestic workers are often left at the mercy of their employers, exposing them to potential harassment, discrimination, and exploitation. It happens due to the lack of political and legal recognition which leaves the domestic workers structurally and procedurally vulnerable to the conditions of poverty. Majority of the domestic workers comes from the states which are least developed as they travel across the country to urban areas to seek jobs. Unfortunately they are paid a wage less than the minimum fixed by the government. This happens due to the fact that most of the domestic workers are illiterate and they are refrained from knowing their basic laws rights as human beings. Even when they are covered by the law, domestic workers suffer severe decent work deficits due to high levels of contravention, fostered in part by high levels of informality, status in migration, and low level of collective organization.

Since the domestic workers mostly migrate from rural areas, it often becomes complicated for them to adapt themselves to the new environment, culture and people which increases their anxiety and frustration. They are abstained from socialising with friends and relatives often times by the employers or they have very less time in their hands for personal nourishment. “Even if we bring lunch to work, there is no time. We’re not considered humans. Even machines need oiling, but people don’t understand it” says Asha who hails from Bihar and has been living in Delhi for years working as a maid in colonies earning almost Rs. 5000 a month. She has been single-handedly raising three kids after her husband’s death. She says that working as a maid is not a problem, but sometimes, the attitude of ‘madams’ are offensive. “Sometimes we need to go to our hometown due to illness or family emergencies. But they do not understand it. They want us to find a substitute if we’re going away. They can celebrate birthdays, but we are not allowed to even visit the family if someone dies” she later added.

Another hurdle which the domestic workers has to face often times are sexual harassments and discrimination due to their caste and colour of the skin. For the sake of the job, the security of their family and due to the fear of victim shaming, they have to keep their mouth shut even if they face sexual assaults at workplace. In Indian society, the stigma associated with domestic work is heightened by the caste system since the chores like cleaning and sweeping are associated with the people belonging to the ‘so-called’ lower castes. The naming of domestic workers as ‘servants’ and ‘maids’ have made them attain an undignified status and inferiority. Though legislations like the Unorganized Social Security Act, 2008, Sexual Harassment against Women at Work Place (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013 and Minimum Wages Schedules are related to domestic workers, there still remains an absence of comprehensive, uniformly applicable, national legislation that promises fair terms of employment and decent working conditions for domestic workers in India.

Another problem that has been surfacing for the domestic workers since the COVID 19 induced lockdown is the extent of their socio-economic vulnerability. According to a conservative estimate, at least 85 percent workers have not received their wages or have been let go by their employees during the lockdown. With the stifling of economic activity brought on by the prolonged nationwide lockdown, Indian domestic workers are now being confronted with increased hardships and financial challenges. The COVID-19 pandemic has made evident the precarious nature of their marginalization and the urgent need to address the situation. The unemployment rate is worse in urban areas, since they do not have many alternatives. “They have this idea of us in their heads, as if we are more unhygienic and unsanitary than others, when we care for cleanliness as much as anyone else” says Guddiya, a domestic help worker from Kambala village in Mohali, whose employers have asked her to not report to work even after the lockdown ended.

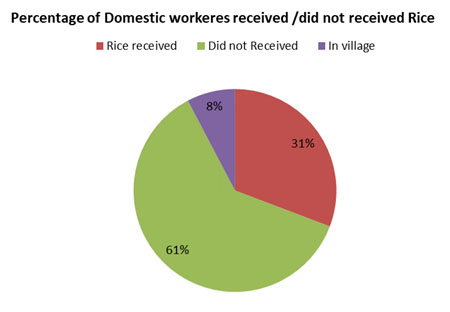

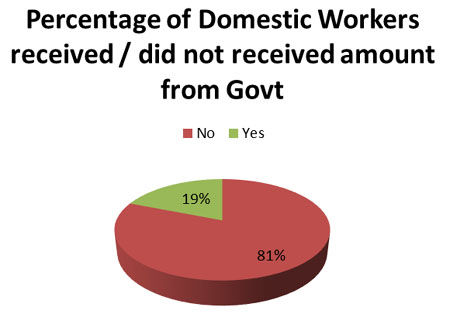

In Assam too, the condtions of the domestic workers have detoriated drastically since the lockdown. Although the government of India has promised free ration and a minimum amount of money in the zero balance accounts, many of them have been deprived of any of those facilities. According to a study made by the Center for Development Initiative, Guwahati, less than half of the percentage of domestic workers have received the free rations. As for the money in the zero balance accounts, only about 20% have received a minimum amount.

With all the savings spent in the lockdown period, she couldn’t afford to stay at Guwahati anymore and hence had to return home and join the tea garden duty as a temporary plucker.

(Geeta who used to be a city maid now works as a temporary plucker)

It is evident from these stories that something needed discussions for too long - the gap in India’s legal framework when it comes to the rights of domestic workers. The reason for this is that traditionally, domestic work has not been counted as real work in terms of contribution to the economy. Our traditional understanding of worker has revolved around industries or offices, and has relegated domestic work to the margins, whether it is performed by spouses and homemakers, or by hired help. This is why labour laws,

designed to protect the interests of workers, apply only to industries or establishments that employ a certain number of people excluding the households.

The female domestic workers are prone to a cluster of injustices, hardships and mortifications at times due to the absence of legal safeguards or welfare measures. They deserve proper safety, protection and actions for empowerment in modern society on the basis of humanitarian ground. Although there has been a lot of discussion about introducing a stronger rights-based authorities for domestic workers in India, nothing real has come out of it. To a great extent, it is thanks to the domestic workers that other women have been successfully entering the paid labour market increasingly these days. At present, there are only two policies regarding domestic workers - the Unorganised Workers Act 2008 and the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace Act 2013. But both of these pieces of legislation are insufficient. While the former fails to give basic rights to domestic workers, the latter fails to address the peculiarities of the domestic work profession, and is thus incapable of addressing the grievances of domestic workers. Had there been a detailed and revised framework to safeguard the interests of domestic workers, their hardships would’ve been a lot easier to manage.

Back to Home Page

Aug 4, 2020

Gitartha P Bhuyan gitartha1@gmail.com

Your Comment if any

|